The Bobbsey Twins

(Richard A. Bloom)

By Amy Harder and Ben Geman

March 6, 2014

Mary Landrieu and Lisa Murkowski have a lot in common.

Both senators come from energy-rich states. Both come from political families. Both have endured major political challenges, only to emerge in leadership positions. It’s true that Landrieu is a Democrat and Murkowski a Republican, but both have come to head the Energy and Natural Resources Committee amid the greatest energy boom the United States has seen in a generation.

Both want to be optimistic.

“I know sometimes it’s hard for Washington to keep up with the times, because they like to stay in the bubble, but there’s a big world out there, and we need to keep up,” says Landrieu, who took the gavel in February.

Yet making great strides on energy issues won’t be easy right now. The truth is, Landrieu and Murkowski are policy-oriented lawmakers at a time when Washington’s appetite for legislation is near an all-time low. Congressional productivity was extremely weak last year. November’s election is expected to suppress it further still, as political calculations eclipse policy needs.

Add Washington’s minimal interest in big, comprehensive legislation in the post-Obamacare era-the last major energy bill Congress passed was in 2007-and a future filled with legislating on the margins looks likely, at least for the rest of this year.

“So much has happened in seemingly such a short, abbreviated time span, and yet the operating rules, if you will-the statutes that govern so much of this-are not only not current, they are antiquated,” Murkow°©ski says.

“If you look at the things that we should be tackling, the great meaty, weighty issues in the energy sector, and we are talking but we are not actually legislating,” she adds. “And so there is a frustration there.”

MANAGING THE ENERGY BOOM

It is hard to overstate the seismic shifts in the energy sector in recent years. Today, the U.S. is pumping more crude oil than it has in two decades, and is on track to outpace Saudi Arabia and Russia as the world’s largest producer. Reliance on imported oil has dropped substantially. U.S. natural-gas production is at record levels, and is already the highest in the world.

The result is that the old narrative-that the United States was running out of oil and gas, and was becoming increasingly dependent on foreign resources-has been blown up. Now, the challenge is managing the boom while also addressing questions about the environmental consequences of hydraulic fracturing, whether to ramp up gas exports and ease the almost total ban on crude-oil exports, and how to address the ever-present specter of climate change.

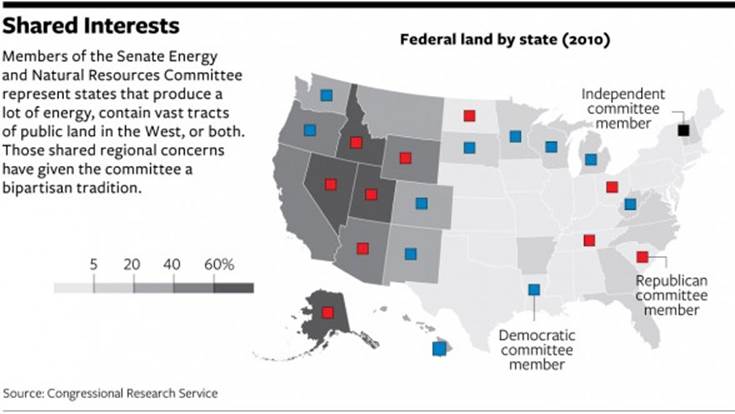

Fast-rising oil production in North Dakota, the gas frenzy in Pennsylvania, and the Texas shale energy boom have probably received the most attention in recent years. But Louisiana and Alaska, from which Landrieu and Murkowski respectively hail, are nonetheless huge energy-producing states where the oil-and-gas industry is a central pillar of the economy. So after several years of Democratic chairmen spotlighting renewable energy, the duo will likely shift the focus back to traditional fossil fuels.

Landrieu is solidly to the right of her caucus when it comes to energy issues. Murkowski is unabashedly pro-oil, but the ranking member is also more moderate on energy than some of her GOP colleagues. For instance, when many Republicans were bashing the Energy Department’s green-energy loan program after the collapse of the federally backed solar-panel company Solyndra a couple of years ago, Murkowski called for reforms but supported the program overall.

The two women have been friends since they were introduced by Murkowski’s father, Frank Murkowski, a former senator who once chaired the Energy Committee. “The Murkowski-Landrieu family [relationship] goes back literally decades,” Landrieu says. And Murkowski makes clear that she sees a kindred spirit in her Democratic counterpart.

“I have had a long working relationship with Mary Landrieu. We have extended that relationship beyond the working side. I have been to her state, she has been to mine; we have really worked to try and understand the similarities and the differences between our energy-producing states.”

Moreover, the only other time in recent memory that two women have led a Senate panel was when Landrieu chaired the Small Business Committee and Olympia Snowe of Maine was the ranking Republican, according to the Senate historian’s office. This is the first time a woman has chaired the Energy Committee.

“It’s really interesting that we have two women running the committee,” says former Sen. Byron Dorgan, a North Dakota Democrat who served on the panel until he retired in 2010. “The Senate is changing, the makeup is changing, and we’ll begin to see this kind of thing, which I think is good for the country.”

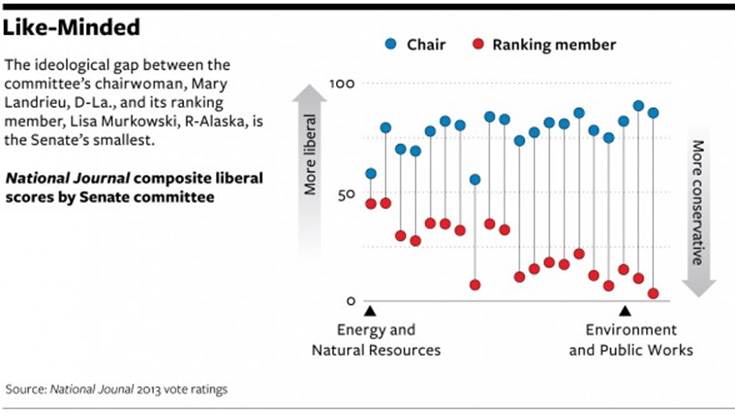

The result could be that the committee is in for a period of bipartisan cooperation that is exceedingly rare in today’s Congress, where it is not unheard of for a chairman and a ranking member to go weeks without a meaningful conversation.

“I suspect both of them will work hard to make the Energy Committee relevant,” Dorgan says.

Lee Fuller, vice president for government relations at the Independent Petroleum Association of America and a former aide to the late Democratic Sen. Lloyd Bentsen of Texas, says the panel “has a history of being reasonably bipartisan in the action it has taken.”

But will that bipartisanship translate into legislation moving through the full Senate?

“That,” Fuller says, “is an open question.”

THE ART OF THE POSSIBLE

It’s not at all clear that there’s enough political space for the Energy Committee-which has been around in one form or another for more than 170 years-to return to prominence.

The panel has played a major role in shaping U.S. energy policy. It produced a 1975 energy law that, in response to the Arab oil embargo, restricted crude-oil exports and authorized the Strategic Petroleum Reserve. A mid-1990s law granted royalty waivers for oil companies exploring the deepwater frontiers of the Gulf of Mexico. Legislation in 2005 and 2007 included provisions that raised appliance-efficiency standards and authorized the Energy Department’s green-energy loan guarantee program.

So what might the current chairwoman and ranking member get done?

Landrieu and Murkowski have teamed up on legislation to give Gulf of Mexico states a bigger share of offshore oil-and-gas revenues and expand availability of revenue-sharing to Alaska and other coastal states. Landrieu wouldn’t offer a timeline for pushing that, however, and says she’ll ensure that the views of all committee members are heard.

“I’m going to actually try my very best to meet with each of them over the course of the next few months to hear directly from them on what some of their views are, some of the challenges before us,” Landrieu says.

Environmentalists worry that neither Landrieu nor Murkowski will prioritize other issues under the committee’s jurisdiction, including renewable energy, national parks, forestry, and climate change. At 51 percent, Landrieu has the second-lowest lifetime score among Senate Democrats on the League of Conservation Voters’ scorecard. Only Sen. Joe Manchin of West Virginia has a lower rating.

Landrieu says the criticism is misplaced.

“First of all, I believe climate change is real and that it’s a great challenge,” she says, adding that she has a long history of supporting expansion of national parks and coastal restoration. “I think a lot of those concerns, or some of them, are unfounded,” Landrieu asserts. “I would just ask people to look at my record.”

Nonetheless, she is unquestionably more pro-industry that nearly all of her Democratic colleagues, including Sen. Debbie Stabenow of Michigan, who is the most vocal panel member when it comes to concerns about increasing natural-gas exports. Yet Stabenow has only good things to say about Landrieu.

“I think she’ll be terrific,” Stabenow says, adding that on natural-gas exports, “we’re having good conversations about the balance.”

Landrieu and Murkowski will certainly use the committee’s oversight powers to shine the spotlight on what they feel are badly needed updates to U.S. policy. For instance, Murkowski has been pushing the Obama administration to relax decades-old limits on crude-oil exports under its existing authority, and she’s eager to move that debate forward.

But if past is precedent, when it comes to actually moving legislation, what Landrieu and Murkowski choose to focus on may well not matter. Former Sen. Jeff Bingaman, who once chaired the committee, failed to get many significant bills through the Senate, including one that would have established a national renewable-electricity standard and another that was aimed at strengthening drilling regulations in the wake of the 2010 BP oil spill.

Bipartisan leadership on a committee, after all, isn’t much help when the overall Senate is stuck. “If gridlock continues, it won’t change much what can be passed,” Dorgan says. He was quick to add, though, that Landrieu and Murkowski have the potential to make progress, given their records.

“The key thing about Mary and Lisa is that they’re not content to be observers,” Dorgan says. “They want to be active. Their legislative history shows that they want to be active on the things that matter.”

“AN UNMITIGATED DISASTER”

Of course, not everyone is thrilled by the Landrieu-Murkowski pairing, which will move the committee to the right. Both women support opening more federal lands to drilling and expanding offshore oil and gas development. And while Murkowski has been far more willing than most Republicans to discuss the dangers of global warming, neither she nor Landrieu is a fan of the administration’s climate-change regulations.

“It has the potential to be an unmitigated disaster,” says Bill Snape, senior counsel for the Center for Biological Diversity, an environmental group. “Two blatantly pro-drilling senators leading both their parties in that committee. It doesn’t get much worse.”

But environmentalists have a firewall: Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid. Snape is hopeful that Democrats’ efforts to help Landrieu, who faces a tough reelection fight this year, won’t tip over into moving legislation to the floor that much of the Democratic caucus opposes. Still, “that is a concern,” Snape says. “We will watch that very carefully.”

Indeed, Landrieu’s reelection race-she is a top target of Senate Republicans, who want to take control of the chamber-will also affect the committee’s productivity. Murkowski is acutely aware of the political crosscurrents running beneath the policy discussions as Landrieu battles for another term and the Senate navigates an election. How much can be accomplished, the Alaskan says, depends on “how much can be navigated in a very politically charged environment.”

“I don’t want us to be in a situation where we are just kind of in a holding pattern for a year,” she says, “that we waste a year as an Energy Committee because of the political process that goes on around here.”

This article appears in the March 8, 2014 edition of National Journal Magazine as Opportunities And Obstacles.

Senate Energy Committee Special Report

Chairwoman Profile: Mary Landrieu

(MANDEL NGAN/AFP/Getty Images)

image005 1064.jpg 2

By Amy Harder

March 6, 2014

For Sen. Mary Landrieu, the next nine months could be the best of times-and possibly the worst, too.

The Democrat now holds the gavel at the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee. The value of that accomplishment is hard to overstate in Louisiana, where energy issues thoroughly dominate the economic and political landscape. The last time a Pelican State pol ran the committee was almost two decades ago, and the position will allow Landrieu to take care of business at home like never before.

But Landrieu is a top target in the Senate Republicans’ drive to take control of the chamber-and she’s vulnerable. In her past three elections, Landrieu has never won more than 52 percent of the vote, and her state is increasingly Republican. She will have to defend everything, especially her support for Obamacare.

Landrieu, however, has an asset that is often in evidence but rarely discussed: She is stubborn.

“My critics would say I’m hardheaded,” she says with muted laughter. “But I would say I’m tenacious and dogged and strong. It’s all in the eye of the beholder.”

No matter how you describe it, Landrieu’s resolve is a defining quality that has helped her amass an impressive legislative record. And she’ll need that strength more than ever as she enters what could be her toughest race yet.

Landrieu, 58, is facing Rep. Bill Cassidy, who has at times pulled ahead in the polls-and who has some very deep-pocketed interests on his side. Americans for Prosperity, the conservative organization funded by the billionaire Koch brothers, has already spent at least $2.6 million to defeat her. And the election is still nine months away.

The GOP has a lot riding on this race, explains Rob Collins, executive director of the National Republican Senatorial Committee. “Louisiana is critical to most pundits’ equations on how we take back the Senate,” he says.

Landrieu is a well-known name in Louisiana, thanks to her three terms in office and a family dynasty that stretches back decades. It’s an open question whether her Energy Committee post will bring her votes, but it certainly won’t hurt her when it comes to raising money. She has already amassed almost $9.5 million, compared with Cassidy’s $5.1 million, according to the Center for Responsive Politics. And she’s beating Cassidy when it comes to donations from oil, natural-gas, and pipeline companies.

History is on Landrieu’s side too. An incumbent hasn’t lost a Senate race in Louisiana since 1932. “Frankly, every one of my races has been difficult,” Landrieu says. “I don’t think this one is going to be any more or any less so.”

Republicans will be taking aim at her support of President Obama’s health care law and her financial backing of Democrats who don’t support robust energy production. “Anytime you’re trying to take out an incumbent, it’s an uphill battle,” Collins says. “But she’s never had an 18-month race like she is in now.”

The truth is that Landrieu, who grew up in New Orleans as the oldest of nine children, has seen a great deal. Her father, Moon Landrieu, was mayor of the city from 1970 to 1978 and was Housing and Urban Development secretary in the Carter administration. Her brother, Mitch Landrieu, is the city’s newly reelected mayor. At age 23, she became the youngest woman ever elected to the Louisiana Legislature.

Landrieu still relies on her father for advice. She recalls a joke he makes sometimes: “I have nine kids, and at least five of them were smart enough not to go into politics.”

“I pushed myself harder than he pushes me,” Landrieu says, “but he’s very supportive.”

One of her most significant legislative accomplishments was a bill signed into law two years ago ensuring that 80 percent of the Clean Air Act penalties that BP incurred from its 2010 oil spill went to Gulf Coast restoration. But chairwoman or not, Landrieu, like all lawmakers, will continue to struggle against the meager appetite for legislation that marks the current Congress.

One example of this challenge is a bill she has championed to delay significant rate increases for flood insurance, vital in flood-prone Louisiana. Landrieu was “chewing people’s ankles off to pass the bill, because of the impact it would have on the state,” says Dan Borne, president of the Louisiana Chemical Association, who first met Landrieu when she was a junior in high school.

The Senate ultimately passed the measure, but it is now hung up in the House (where Cassidy is leading the push for the reprieve).

And for all her doggedness, Landrieu hasn’t yet succeeded on the issue most important to her: revenue-sharing for coastal states, which would give them a cut of the drilling royalties akin to what landlocked energy-producing states get today.

“Revenue-sharing is a means to an end,” says Tom Michels, who was a senior Landrieu aide for almost six years. “She’s not simply looking for money; she’s looking to save the coast.”

From her Energy Committee perch, Landrieu has the best chance she will probably ever get to pass such legislation. The panel’s ranking member, Lisa Murkowski, is a cosponsor of the bill, which simply speeds up what current law already requires in 2017 and removes a cap on how much money a coastal state can receive in royalty dollars. To succeed, however, Landrieu must have at least the support of her committee, whose Democratic members are mostly to the left of her on energy issues, so she remains cautious about her chances.

“I don’t have a time frame on that yet,” she says. “It’s been a concern of mine since the day I stepped into the Congress, and I will do everything I can, and use everything I can, to make it more fair.”

But some observers are more openly optimistic about the bill’s prospects-among them former Sen. Bennett Johnston, who was the last and only other Louisianan to chair the Energy panel (from 1987 to 1995).

“I think she can pass it through committee,” he says. “And she thinks she can pass it through committee.”

This article appears in the March 8, 2014 edition of National Journal Magazine as Mary Landrieu.

National Journal

Magazine / Senate Energy Committee Special Report

Ranking Member Profile: Lisa Murkowski

By Ben Geman

March 6, 2014

In another political age, this might be the start of a bright year for Sen. Lisa Murkowski of Alaska, the top Republican on the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee and a strong advocate of the oil industry.

Fellow oil-state Sen. Mary Landrieu just became chairwoman of the committee, and the Louisiana Democrat-who sits to the right of her caucus on energy-sees eye-to-eye with Murkowski on plenty of things.

But Murkowski, 56, freely acknowledges that the Senate’s limited agenda presents few chances to act on anyone’s policy goals. And so the blessings are bittersweet.

“You have to have that level of patience,” Murkowski said. “But where I am not as patient is with the political messaging, pushing back on what I think are good, solid initiatives because they don’t necessarily benefit the majority [party] at the time.

“It seems that I am getting a little more impatient as these years are going on, and I am just not seeing the accomplishments coming out of the Congress.”

Gridlock, in short, annoys the daughter of Frank Murkowski, himself a senator for more than two decades and a former Alaska governor. While there’s little doubt that family ties helped steer her toward politics-after she served in the Legislature, her father appointed her to the Senate in 2002 when he vacated the seat to become governor-it was the policy side and the ability to shape major changes that truly caught and held her interest.

Andrew Halcro, who served with Murkowski in the Alaska Legislature in the 1990s, tells a story of Murkowski toting around marked-up folders as they walked through the state Capitol. “She turns to me and says, ‘Do you ever get the feeling that you and I are the only two people on these committees that really read these bill packets?’ ” Halcro said.

“She is genuinely curious,” said Halcro, now president of the Anchorage Chamber of Commerce. “She wants to learn. She actually does the heavy lifting herself.”

Abandoning her original ambition to be a teacher, Murkowski studied law and eventually found politics. “In retrospect I would not have been a good teacher, because I would have given those kids so much homework every night,” she said. Perhaps not so much as she gives herself. “It’s a serious job,” she said. “I need to be informed, and as fabulous as my staff is, I don’t expect them to be the senator.” But when it comes to energy policy, Murkowski is increasingly confronting a discouraging question: Informed to what end? Major legislation stands little chance in an election year-a frustrating state of affairs for a senator who doesn’t spend a lot of time seeking attention for herself.

“I think she is much more interested in doing the work, much more interested in her connection with people in Alaska,” said McKie Campbell, her former staff director on the committee and a longtime friend. “I think she is interested in having a large impact on national policy, but not as interested in being a national figure.

“For a senator, there is very little ego,” Campbell added. “That is sometimes to the frustration of her staff, who would like her to go out and be on Sunday shows more, have a higher profile.”

In 2010 Murkowski did become a national political figure as she sought a second full Senate term and faced one of the biggest political hurdles of her career.

Murkowski lost her 2010 primary to Joe Miller, a Sarah Palin-backed tea-party challenger. So she launched an improbable write-in campaign without the National Republican Senatorial Committee’s support-and won. It was the first successful write-in campaign for the Senate since the 1950s.

Murkowski has forged her own path in other ways, too. She’s a woman in the largely male Senate, and she’s among the GOP’s moderates on social issues. She supports gay marriage and abortion rights, although she gets some credit from antiabortion activists for her votes on certain funding and abortion-restriction measures.

“I think that Lisa’s voice is a really important one in articulating points of view that may not be held by some of our colleagues,” said Sen. Susan Collins, a moderate Republican from Maine and a close friend of Murkowski’s.

Murkowski calls 2010 a clarifying moment.

“It was one of those experiences that you go through that really causes you to search pretty deep in yourself to find out, why am I doing this? Once you have identified why you are doing it-it’s because you love a place [Alaska] so deeply-you kind of lose the fear of being the only one on your side that is voting ‘no’ or ‘aye,’ ” Murkowski said.

“I try to be a good team player with my conference, and I think I am respected as one, but I think I am also respected as one who has perhaps a little more independent trail to take, and I am happy with it.”

But how happy can she be in this Senate?

Washington is constraining for Murkow- ski, who enjoys skiing and biking in her home state. But she is poised to become a more powerful senator if Republicans gain control of the chamber in November. That would make her chairwoman of the Energy Committee, and of the Appropriations subpanel that oversees spending for the Interior Department and the Environmental Protection Agency. And when it comes to energy, Murkowski sees chances to progress in other ways. Recently she has been pushing the Obama administration to relax the decades-old restrictions on crude-oil exports-an issue on which Republicans haven’t yet reached consensus.

“Maybe from the [2010 election] experience that I went through,” she adds, pausing to find the right words, “there is no fear of losing here, because what I am trying to do is not advance a bill. I am trying to advance the thought, the dialogue, the debate on this.”

And she’s willing to absorb some bruises along the way. Back in 2009 she ripped up ligaments in her left knee in a skiing accident south of Anchorage that sent her tumbling hundreds of feet. “She’s back,” says Campbell, “still skiing the steep stuff.”

This article appears in the March 8, 2014 edition of National Journal Magazine as Lisa Murkowski.

Senate Energy Committee Special Report

Committee Staffers: Top Republicans

image008 289.jpg 2

Karen Billups, Patrick McCormick and Robert Dillon.(Photos: Richard A. Bloom)

image009 244.jpg 2

By Clare Foran

March 6, 2014

Robert Dillon

Minority Communications Director

Dillon grew up in Indiana and Alaska and describes himself as an “ink-under-the-fingernails” journalist. He spent much of his career covering energy, climate change, and regulatory policy for a variety of media outlets, including the Fairbanks Daily News-Miner.

He sees his job on the committee as the other side of the same coin.

Dillon’s primary responsibility, as he puts it, is the same as when he worked in journalism-to get information to the public in a timely fashion. His work involves reacting to administration policy and the actions of Senate Democrats, as well as circulating press releases and policy papers to further the debate on energy issues and advance the position of Republican committee members.

What’s a typical day? For Dillon, 45, there’s no such thing. “The only thing typical,” he says, “is that whatever I come in with on my list of things to do, those aren’t the things I end up working on that day.”

Patrick McCormick

Minority Chief Counsel

Between private-sector and federal-agency experience, McCormick has worked on energy policy from many angles. But his work as minority chief counsel has given him a unique vantage point and a broad view of the landscape.

“It’s fascinating to look at the bigger picture,” he says. “Our work in the committee is to constantly ask: Does the United States have an energy system that can act in the public interest?”

McCormick has lived in Baltimore for more than 30 years and previously led the regulated-markets and energy-infrastructure practice at law firm Hunton & Williams in Washington. Before his almost 20 years in private practice, he was deputy assistant general counsel for electric rates and corporate regulation at the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission.

The Philadelphia native weighs in on legislation that passes through the committee and makes sure bills are primed to do what their sponsors intend. He also advises Republican committee members on oversight activities. McCormick, 57, says he doesn’t mind getting into the weeds on energy and regulatory policy-in fact, he enjoys it.

Karen Billups

Minority Staff Director

For Billups, energy has been a fitting career focus. When she was growing up in Texas, she says, energy was everywhere. She was educated against a backdrop of oil wells and derricks-her high school’s parking lot even had an oil well in the middle-and she studied energy policy at the University of Texas Law School.

After rising through the ranks of the committee staff during two tours of duty, Billups, 51, was named staff director at the beginning of last year. Earlier, she was the panel’s counsel for energy issues, senior counsel, and chief counsel. Billups also worked as director of federal affairs and Washington counsel for Entergy.

The most challenging part of her job is that committee staffers come to her when they have a problem they can’t solve. “My days are full of questions that nobody else knows how to answer,” she says. “I can’t say I always know the answer either, but I think I best serve as a sounding board.”

She added, “I love the variety and the challenge and getting to interact with people all day.”

This article appears in the March 8, 2014 edition of National Journal Magazine as Top Republicans.

Special thank to Richard Charter